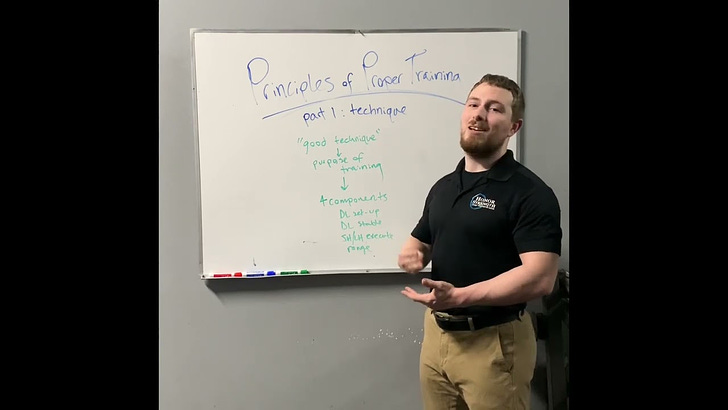

Principles of Proper Training part 1

What is good technique, why is it important, & how do we achieve it?

This is part 1 of a 4 part series, “Principles of Proper Training.”

Please subscribe so you can be notified of additional installments and support my work.

You may have been told to use “good technique”.

But what exactly does that mean, why is it important, and how can we do it?

First you must understand, as a coach or an athlete, exercises are tools for producing adaptations. What the adaptations are, precisely, will illuminate the best exercises and the way in which you should perform them within a training program.

If our goal is hypertrophy or maximal strength, then the way we use exercises will be to maximize mechanical tension for enough total time under tension to reach the adaptation threshold.

The way in which we perform an exercise should maximize mechanical tension in the intended tissues while minimizing structural damage or compensation from other tissues.

If your intention is training your biceps, it’s generally less efficient to contract your lower back to swing the weight up.

Good technique in regards to hypertrophy basically refers to how effectively you produce mechanical tension in a target muscle, and how efficiently you produce that tension without the use of other muscles to assist.

Technique can diminish over the course of a set, especially as you fatigue and maintaining or further increasing the tension becomes incredibly painful. At this point, the technique becomes more important for injury prevention. However, taking a muscle to “failure” eventually becomes necessary to reach the adaptation threshold.

Taking a muscle to failure is straining to the point you truly cannot execute one more concentric repetition even with intense mental focus. The ability to strain is a major limiting factor for novice athletes, or even intermediate level athletes, who want to reach the next level.

In fact, training to failure with proper technique is exponentially harder than training brutally hard with disregard for technique. This will be discussed at length in part 4 of this series.

So with all of that said, the first principle of proper training is to optimize movement quality for your intended purpose.

Simply choose the right tool and use it the best way.

Or even more simply, use good technique.

Good technique is that which maximizes force production and mechanical tension while minimizing systemic stress, collateral tissue damage, and injury risk - so you can train harder & more often.

The 4 Components of Technique

So how do we ensure good technique?

There are 4 components of technique: set-up, stabilization, execution, and range.

I learned the first 3 components from Ben Pakulski; it’s important to give credit when it’s due.

Set-up

The first is the set-up. The purpose of a set-up is to set the stage for maximal stability.

The more stable a joint is, the more mechanical tension you can produce at the intended muscle(s), and the less risk for injury. You also increase the potential for force production, so this is relevant for increasing a muscle’s ability to produce force and overcome resistance - maximal strength.

This is why you can lift 1,000 pounds with a leg press but there’s no way in hell you’re squatting that. You probably wouldn’t even stay standing with that on your back.

The set-up is different for each exercise, as you might imagine.

Stabilize

The second component is stabilization. Often, set-up and stabilization occur simultaneously. However, there are two key differences: improper set-up can work against your ability to stabilize, and stabilization must occur throughout the movement.

For example, if you set-up for a deadlift and the bar is in front of your legs, that is a set-up inefficiency. If your set-up on a deadlift is correct but you don’t brace your torso and create intra-abdominal pressure before you lift, your stabilization is inefficient.

Stabilization inefficiencies have many origins. The most common is simply lack of knowledge, followed by inefficient set-up, structural imbalances, and soft-tissue restrictions.

Execute

The third component is the execution.

How can you tell which muscle is contracting the hardest? When a muscle contracts, it will shorten, thus the origin will come closer to the insertion. It’s that simple, albeit your ability in this regard depends on your anatomy knowledge. It’s easy for me to see compensatory patterns after watching people move and studying anatomy for thousands of hours.

In regard to hypertrophy and maximal strength, there are optimal firing patterns to maximize mechanical tension, produce the most force, and lift the most weight, depending on the exercise and the unique anatomy of the athlete.

As a simple example, if you perform a biceps curl, the insertion of your biceps on your forearm should come closer to the origin of your biceps which is on the coracoid process (short-head) and the supraglenoid tubercle (long-head).

Yes, there are variations in exercises and techniques that can target one head, which further demonstrates this 3rd component: if we externally rotate the shoulder, we shorten the long-head more and the short-head less because the insertion moves closer to the origin of the long-head and away from the coracoid. If the arm is extended behind the body, this further increases the length of the short-head.

We can become quite nuanced once we understand anatomy, but remember this basic principle: if you want to contract a muscle, and thus maximize tension in that muscle so it grows, bring the insertion closer to the origin.

Range

The final principle is range.

Range is important because tension is increased at end-range in both shortened and lengthened positions, but also because a muscle will adapt to the range you train it in. If you perpetually train in a partial range of motion the tissue may adapt into that shortened position, and you will only develop strength in that range of motion.

Remember, your body will adapt specifically to the demands you impose upon it. Conversely, if you train in longer ranges of motion, you can experience an anatomical adaptation where the length of the muscle will increase, in addition to building strength in a full range of motion.

Generally full range of motion is the best idea but there are certainly many uses for partial ranges of motion.

Summary

Optimize the quality of your training and you’ll achieve more in less time with less pain.

I truly hope this helps you increase the productivity of your training, and as always, reach out to me with any questions.

If you found this valuable, please subscribe so you can support my work and receive articles directly to your email as they are released.

In strength,

Daniel J. Furtado, CPT, LMT, Owner of Honor Strength

www.honorstrength.com